The Question

I, like many others, started learning to play piano when I was around 8 years old. I took lessons, learned songs, and gained an appreciation for the instrument. I have been playing (with some breaks) until today. Although I have been playing for a while, it wasn’t until taking my first music theory class in college that I started thinking deeply about why music is constructed in the way it is. In the theory class, we learned about chord progressions and voice leading but I found that as I dug deeper into the theory, there were fundamental parts I didn’t understand.

Here is a picture of the piano keys:

Piano keyboard layout

Piano keyboard layout

As you can see, the keys are structured in a very intentional way; there is a common pattern across the keys. There is a set of 5 black keys that repeat, a set of 7 white keys that repeat, and a set of 12 total notes (white + black) that repeat.

In fact, these numbers (5, 7, and 12) are fundamental to western music. The most fundamental scales are the 5-note pentatonic scale, the 7-note diatonic scale, and the 12-note chromatic scale. One might ask: why these numbers? There are infinite frequencies that one could choose, so why choose discrete sets of 5, 7, and 12 notes for these common scales?

In this blog post I will explore this question and give a backing for why these choices are not arbitrary, and in fact have interestin properties related to fundamental principles about harmonics. When I first found this way of thinking about music, it helped me realize the beauty of the western music system that we hear in pop, rock, and jazz. I have tried to write this in a way that no music background is required to understand it, so without further ado let’s dive in!

Harmonics and Overtones

For those of us who have (maybe begrudgingly) taken physics classes, there is a concept of harmonics that appears everywhere. Let’s take plucking a guitar string for example. When you pluck the string, it vibrates at a certain frequency and it produces a noise at that frequency. Frequency \(f\) is simply how fast the string is vibrating. Higher frequencies sound like higher-pitched notes, and lower frequencies sound like lower-pitched notes Wavelength \(\lambda\) is the distance that a wave’s shape repeats. Wavelength and frequency are inversely related:

$$f\alpha\frac{1}{\lambda}$$ Intuitively, plucking a shorter string creates a higher-pitched sound and vice versa. Depending on how fast a string is vibrating (the frequency), there are harmonics that arise that produce different sounds. Let’s first look at it graphically:

From Wikipedia

The first harmonic is the “easiest” (lowest energy) way to make the string vibrate. The second harmonic is the next easiest, and so on. Let’s say the first harmonic has a wavelength of 1. This means that the frequency of the first harmonic is 1 (in the ratio). Therefore, since the second harmonic has wavelength of ½, the frequency is 1 Furthermore, the third harmonic has a frequency of 3. We can see that the ratio of frequencies from the second to first harmonics is 2, and the ratio of frequencies from the third to second harmonics is 3/2. These ratios are important, and we will come back to them shortly.

Building an Instrument

Now we are ready to use this knowledge to build an instrument. When one plays a note on an instrument (i.e. a note at a frequency \(f\)), although the note at frequency \(f\) is the fundamental tone, there are other frequencies that are also present; these frequencies are called overtones. For example, if I play an A at 440 Hz on a flute, A is the fundamental tone, but the frequencies of 880 Hz (A an octave up, and the second harmonic) and 660 Hz (E, which is a fifth above A and is the third harmonic) are also present. Here is a video of Leonard Bernstein demonstrating overtones. If one plays a note as well as one of its overtones, it sounds good to the ear. This is why octaves (which are frequencies separated by a factor of 2) sound good when played.

Another concept we can use to build our instrument is equal-temperament tuning. This means that the ratio of frequencies between any two subsequent notes should be the same. This is convenient for us since it means that transposing music (moving a melody up or down some notes) is trivial since it doesn’t change the relationships between the notes. Furthermore, pianos and other instruments such as guitars have equal-temperament tuning.

The simplest instrument we could construct then would be a one-note instrument that consists of some frequency \(f\) and all the power of 2 factors of \(f\), such as \(2f\), \(4f\), etc. In Western music, these are all thought of as the same note since the frequency of each subsequent note is separated by a factor of 2, which is an octave. The one-note instrument introduces an important concept: we want to be able to play octaves on our multiple-note instruments. However, the one-note instrument is boring since we are very limited in what we can play, so let’s add more notes.

Now let’s build a two-note instrument. We will essentially add a note between each octave. Enforcing the equal-temperament rule, we must have the ratio between any two notes equal to \(\sqrt2\). For our one-note instrument, each subsequent note was the second harmonic of the first note since the frequency was doubled. The next harmonic is the third harmonic and the third harmonic has \(\frac{3}{2}\) times the frequency of the second harmonic. We can see that \(\sqrt{2}\) is pretty close to \(\frac{3}{2}\). Thus, we can almost play the fifth with our two-note intrument. Ideally, we want to approximate the interval of a fifth (i.e. \(\frac{3}{2}\) times the frequency of another note) as close as possible since fifths sound good to the ear. However, we can see that with this construction, we miss the fifth by a decent amount, so it would be ideal to be able to play fifths more accurately.

Now let’s build a five-note instrument. Since five notes make up an octave and we want equal-temperament tuning, the ratio between any two subsequent notes is \(\sqrt[5]{2}\). We can see that \(\sqrt[5]2^3 = 1.516\), so using the five-note scale lets us play intervals that are closer to fifths compared to the two-note instrument. In contrast, if we built a four-note scale the closest ratio we can get to the fifth is \(\sqrt[4]2^3=1.414\), so we would prefer the five-note scale over the four-note scale.

The Equation

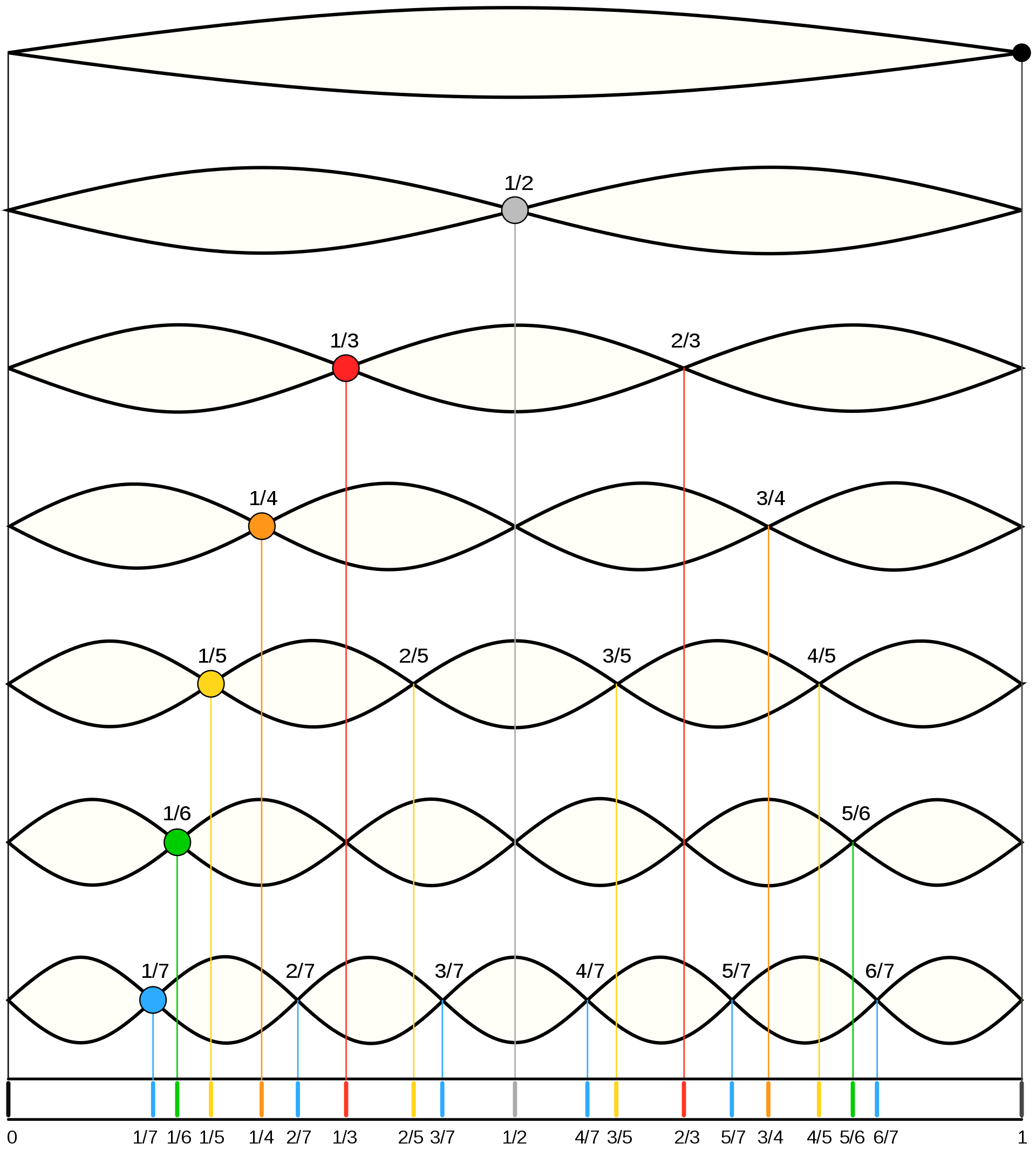

Now we have some intuition into an aspect of what makes a good scale: we want to have the fifth encoded into the scale as closely as possible. Let’s abstract this concept a bit. For any integer \(n\)-note scale, the ratio between any two notes is \(\sqrt[n]2\). So we want to find an integer \(n\) such that for some integer \(k\),

$$\sqrt[n]2 ^k\approx\frac{3}{2}.$$

We can rewrite this idea as trying to find an integer \(k\) such that \(1\leq k < n\) such that we minimize \(k - \log_2(\frac{3}{2}) * n\). So we can see that to find the optimal \(k\), we can solve

$$k=round(\log_2(\frac{3}{2}) * n),$$

where \(round(x)\) rounds \(x\) to the nearest integer.

Let’s see what we get for different values of \(n\).

We can use the following Python code to do it programmatically:

for n in range(1, 20):

k = round(n * math.log2(3/2))

fifth_error = 3/2 - 2 ** (k / n)

print(n, k, fifth_error)

Let’s look at the output:

Data output for python code

Data output for python code

We can see that the smallest errors between the perfect fifth and the closest ratio we can reach with an \(n\)-note scale occur for \(n=5\), \(n=7\), and \(n=12\). \(n=12\) has the smallest error with only 0.0017. This is very cool since those numbers represent the pentatonic, diatonic, and chromatic scales. Extending this concept, we can see that \(n=17\), \(n=19\), and \(n=24\) are also very close to approximating the fifth with equal temperament. All these numbers are common tunings used in scales around the world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have derived many common tunings by simply seeking to approximate the fifth as closely as possible using an equal-temperament approach. From this study, we can see that there are real reasons to choose certain number of notes in a scale based on harmonics. I will note that this method is simply a way of understanding why scales have certain numbers of notes and is not the way that the scales were generated historically. Specifically, the western diatonic and pentatonic scales are not equally tempered. However, this is still a valuable and interesting way of thinking about music scales.