Why Exchange Clocks Matter

In high frequency trading (HFT), time is literally money. An edge of a few microseconds could translate to millions in profits. The most popular markets for cash products (equity, bonds, etc.) are in New York (NYSE, Nasdaq), while the most popular futures and options market is in Chicago (CME). Since cash and futures influence each other, getting data between New York and Chicago as fast as possible is important. If one has the fastest transmission time, they can look for price discrepancies and book profits.

An example of implementing this arbitrage strategy is in 2009, Spread Networks layed down an ultra high speed fiber-optic cable between Chicago and New York. In order to do it, they bored through mountains in Pennsylvania in order to make the path of the wire as straight as possible, reducing the distance information had to travel. In total, the project cost $300 million. The result? They can send information in 13.3 milliseconds round trip, 3 milliseconds faster than the competition at the time. So we can see that a 3 millisecond edge is worth at least $300 million.

Map of Chicago to New York, taken from here

Map of Chicago to New York, taken from here

Now, companies such as McKay Brothers use microwave communication to transmit information in 8 milliseconds round trip. We are close to reaching the lower limit on transmission time since information can’t travel faster than light (i.e. microwaves). With many modern HFT firms competing on the microsecond scale, it is important to understand how exchanges process orders and ensure fair play. For example, if I trade one microsecond faster than a competitor, the exchange needs to ensure that my order gets processed first.

Having accurate clocks helps prevent fraudulent activity. One illegal form of market manipulation is front running. Front running is when a firm “cuts in line” to make money off of orders. For example, let’s say someone submits an order to a broker to buy large size of shares of a company. Since the broker sees that this order will increase the price of the company stock, they can put in buy orders from their own account before their client’s orders and book a profit. If exchange clocks are imprecise–say they are only accurate to one second–and a HFT can execute many orders in a second, then the exchange could reorder all the trades in the second in any way they want, without being detected by an auditor! This is clearly a problem, since in trading, when there is easy money to be made through fraud, people typically take advantage of it…

Accurate clocks are also important to settle trades correctly when abnormal events happen. One example of this is the 2010 flash crash. After the market closed, FINRA decided to cancel trades made after 2:40 PM and at a certain price depending on the security. Therefore, having accurate trade logs was essential to apply this rule. If there are any discrepancies about who traded, the exchange should be able to accurately retrace every trade in order. For these reasons, there is a need for accurate clocks across all computers in the exchange.

Laws In Place

There are many laws in place that exchanges must abide by related to how accurate their clocks need to be and how closely the clocks need to be synced with National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) clocks.

1998 NASD Order Audit Trail System (OATS) rule 6953:

This rule came after a 1996 SEC report found that dealers did not always act in the best interest of their clients. In 1998, FINRA established the OATS audit system to track transactions made in the market. Rule 6953 required all time stamping devices to be synchronized within three seconds of the NIST atomic clock. The three second rule required clocks without second precision to be discarded. In 2008, this rule was replaced by rule 7430 which required clocks to be within one second of NIST.

2012 Consolidated Audit Trail (CAT) rule:

In 2012, the SEC implemented the CAT rule, which was a more expansive version of the OATS rule. This rule required every registered broker and broker-dealer to keep track of every order and send it to a central location every day. This means every trade can be monitored by the SEC. Furthermore, timestamps were required to be recorded in milliseconds. Lastly, timestamps for automated orders were required to be within 50 milliseconds of NIST and timestamps for manual orders were required to be within 1 second of NIST. Automated orders are machine-initiated trades (algorithmic trading), while manual orders are human-initiated trades.

How Does the NIST Atomic Clock Work?

In 1968, the second was defined (and remains defined) as a certain number of cycles of radiation corresponding to the transition between two energy levels of the ground state of the cesium-133 atom at absolute zero. Essentially, the cesium atom oscillates, and by counting the oscillations, we can get a consistent measure of time. In fact, when the cesium atom changes energy levels, it emits light (photons) which can be measured by using the photoelectric effect.

An atomic clock has a beam of cesium atoms that absorb energy in the form of microwaves and vibrate. The frequency of the microwaves is varied until a maximum number of cesium atoms change state, indicating that the correct frequency has been reached.

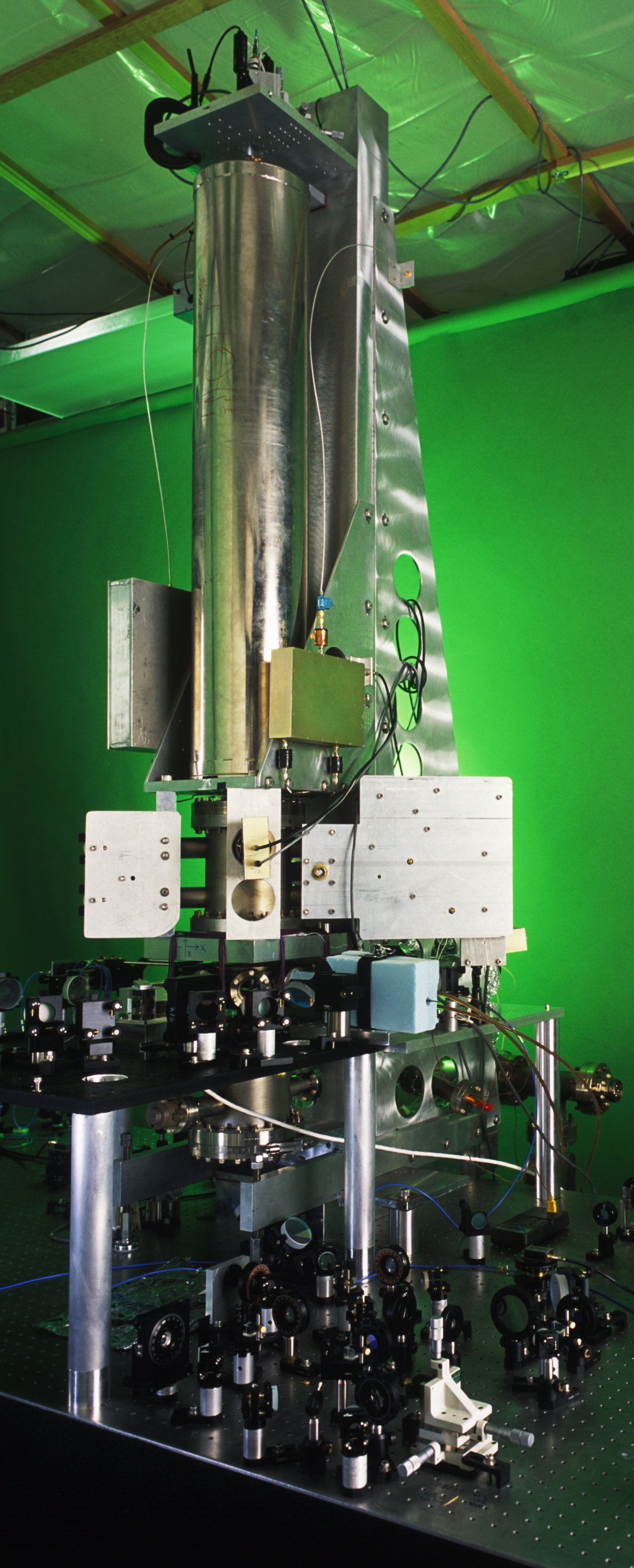

NIST-F1, taken from here

One of the principle NIST clocks used by stock exchanges is NIST-F1 which lives in Boulder, Colorado. One factor that is controlled for in this clock is the temperature of the atoms. Since the second is defined at absolute zero, NIST-F1 uses lasers to slow the movement of the atoms so that the temperature is close to absolute zero: “a few millionths of a degree above absolute zero,” according to their website. Traditional cesium clocks measure atoms that are quickly moving through the air, so they only have a few milliseconds to adjust the microwave frequency. In contrast, since NIST-F1 has close to stationary atoms, they have around a second to tune the frequency. This means that the frequency is more accurate than other clocks, leading to more accurate times.

As of 2013, NIST-F1 has an uncertainty of \(3*10^{-16}\), which means that it would take 100 million years for the clock to be off by a second, according to their website. Impressive! And certainly accurate enough for stock exchanges.

How are Clocks Synced?

Given the laws described above, a practical problem that exchanges have is how to sync their clocks to the NIST standard. The simplest way to do it would be to connect to a service that streams the NIST time out and read it into your clock to sync it. However, doing it this way will result in your clock being off by the time it takes for the signal to travel to you, which is not insignificant (it is on the scale of milliseconds).

Satellite clock syncing, taken from here

Satellite clock syncing, taken from here

The way that this problem is amended is by having a third party that syncs the clocks. For example, if I want to sync my clock in Chicago with NIST, which transmits data from Boulder, then we can both connect to a satellite \(S\) that is equidistant to both Boulder and Chicago. The satellite has a clock on board, and when it receives the data from Boulder and Chicago, the satellite records the time differences $$\Delta t_{S, Boulder}=t_S-t_{Boulder}$$ and $$\Delta t_{S, Chicago}=t_S-t_{Chicago}.$$ From this, we can infer the difference between the two clocks \begin{eqnarray} \Delta t_{Chicago, Boulder} &=& \Delta t_{S, Boulder} - \Delta t_{S, Chicago} \\ &=& (t_S-t_{Boulder}) - (t_S-t_{Chicago})\\ &=& t_{Chicago}-t_{Boulder} \end{eqnarray} Now I can adjust my clock until \(\Delta t_{Chicago, Boulder} = 0\) and the two clocks will be synced!

If the satellite is not equidistant from both clocks (i.e. \(d_{S, Chicago}\neq d_{S, Boulder}\)), then we can correct for this error as long as we know where the satellite is relative to both clocks since we know that the data travels at the speed of light. The ionosphere and troposphere layers of the atmosphere may also introduce error terms that must be taken into account in practice.

Conclusion

As we can see, clocks in stock markets are vital for trading to function fairly among all participants. However, coming up with accurate clocks and syncing them has many layers: building the clock, syncing the clock. I hope this article provides some new insights into how a seemingly simple aspect of markets works.

References

- https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/jres/121/jres.121.023.pdf

- https://www.nist.gov/pml/time-and-frequency-division/time-realization/primary-standard-nist-f1

- https://jpm.pm-research.com/content/37/2/118

–