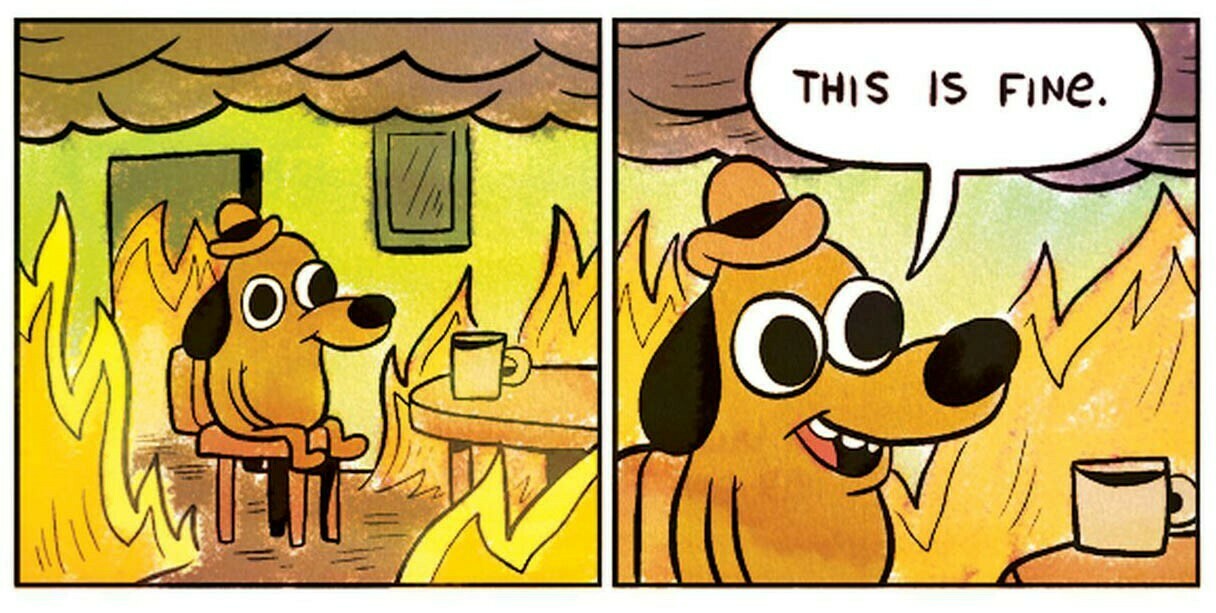

Debugging prod after shipping on Friday

Your job as a software engineer

Every line of production code is a bet on speed, safety, and correctness. When you ship software, you are balancing:

- Getting it done fast -> shipping faster means the feature appears earlier for customers and ultimately the business makes more money

- Not introducing bugs -> bugs can cause outages or other errors that lead to losses

The problem is that anyone that has worked with software knows that no matter what, you cannot guarantee that your shipped software will not have bugs. In fact, your software will always have bugs. No matter how many “lgtms” you get on your pull request, bugs always find a way of creeping in.

Having worked as a software developer in the trading industry, I have seen how software bugs directly lead to monetary losses. In fact, entire firms have gone out of business due to software bugs. The most famous example of this is Knight Capital. They had a bug that caused their automated trading software to repeatedly buy stocks, causing them to lose 440 million dollars in less than an hour and ultimately go out of business.

As a software developer at a trading firm, a key component of your job is to avoid catastrophic errors at all cost. This applies more generally outside of trading, however. An outage can cost the company millions of dollars every hour, and there are other ways software can cause direct or indirect monetary losses. Every software developer should be conscious of risk when they are pushing new code. Every software developer is a risk manager.

Can we squash all the bugs?

There is only one way to never introduce bugs into your software: never push new code. But your whole job is to push code, so we can’t do that…

I propose that as software engineers, we shift our mindset from “I should not have bugs in my code” to “I should manage the risk of new bugs.” You should have bugs in your code if you want to ship the best software. A software team has limited capacity, and the tradeoff between new features and reducing bugs should be seriously considered. We need a framework to make decisions about how much time you should dedicate to a task in order to manage the risk of bugs.

The main idea is that for any feature you are building you need to have a sense of

- The value your feature provides

- The risk of your feature in production

The value your feature provides is proportional to how long it is available to users. In other words, the longer you delay a new feature, the less overall value it will bring to the company. The risk of the feature is difficult to quantify since it is unknown. However, based on experience, there are a range of bugs that are possible for a given code change. In general, we should think of the worst case scenario that could happen when implementing a new feature.

Once we have an idea of the value that a feature provides and the risk of bugs, we can weigh these against each other. There should be a point where waiting longer to release a feature will not reduce the risk of bugs by enough, and that is when we should release the feature.

This framework helps us weigh the importance of features against the risk of bugs. Focusing only on reducing bugs ignores the reality that not all bugs matter equally, and that delaying a feature has real, measurable costs. Trying to “just reduce bugs” has no natural endpoint, but a risk-based framework gives you a principled stopping rule for when a feature is safe enough to ship.

Formalizing the tradeoff

We can formalize this idea as follows. First, let’s assume we have a feature that we are working on and we are trying to find the best time \(t\ge 0\) to release the feature. First, our feature has a value to the business \(V(t)\). \(V(t)\) is the cumulative business value gained if the feature is live from \(t\) onwards. A simple value function is \(V(t)=v*(T-t)\), where \(T\) represents the time the feature will be deprecated. Second, we have the cost of the bug \(C\), which is a random variable. This can capture small errors to catastrophic errors. Lastly, let \(p(t)\) be the probability of a bug occuring at release time \(t\). \(p(t)\) should decrease with time.

Now, we can see that we are trying to maximize $$\mathbb{E}[X(t)] = V(t) - p(t) * \mathbb{E}[C].$$ This function represents our expected value of pushing the feature out at time \(t\), accounting for the loss due to bugs. As time increases, \(V(t)\) decreases, but \(p(t)\) also decreases. Delaying release reduces expected bug cost but also sacrifices business value. Waiting longer is beneficial only as long as the reduction in expected bug cost exceeds the value lost by delaying the feature.

How stakes dominate the equation

In some cases, when the value of the feature is enormous, just getting it out there as fast as possible and risking bugs makes sense. This is the “move fast and break things” mentality that startups have. However, when the cost of an error is high, it makes sense to be more careful and implement more safeguards. Imagine if an airplane’s flight-control team had the “move fast and break things” mentality! A typo in a marketing banner is annoying but a bug in a trading algorithm is catastrophic.

The most important variable in the equation is the severity of possible bugs. It is important to not underestimate this, and instead assume that bugs have the potential to be more severe than expected. For example, Therac-25 was a radiation therapy machine used for treating cancer. Between 1985 and 1987, at least six patients received massive radiation overdoses, resulting in serious injury and death. These failures were not caused by exotic edge cases, but by relatively mundane software race conditions and operator input timing.

Earlier radiation machines included hardware interlocks that physically prevented unsafe doses from being delivered. Therac-25 removed many of these safeguards and relied almost entirely on software for safety. When the software entered an invalid state, the machine could deliver lethal doses while reporting normal operation to the operator. From a risk perspective, the probability of these failures may have seemed low, but the severity was catastrophic. In terms of the framework above, even a small probability multiplied by an enormous cost produces an unacceptable expected outcome. This is a regime where speed and convenience should have been dominated entirely by risk mitigation, and where multiple independent layers of protection were necessary.

Mitigating risk

Even though your prod code should have bugs, we obviously want to minimize them as much as possible. Here are some strategies for mitigating risk:

- Have multiple layers of checks and make sure multiple people review the software

- Be able to roll back code

- Be cognizant of the risk of a task before pushing to prod, if it is more risky think through all the things that can go wrong and monitor it closely

- Practice fire drills for when things go wrong so the team is prepared to fix them quickly

- Promote a culture of blamelessness, where engineers can surface risks, mistakes, and near-misses early without fear, so issues are caught before they reach prod

- Invest in strong monitoring, alerting, and dashboards so issues are detected quickly

Bugs are an unavoidable part of shipping software, but catastrophic failures do not have to be. By treating releases as risk decisions, developers can move faster where it is safe and slow down where it matters. The goal is not perfect software, but informed, intentional tradeoffs.